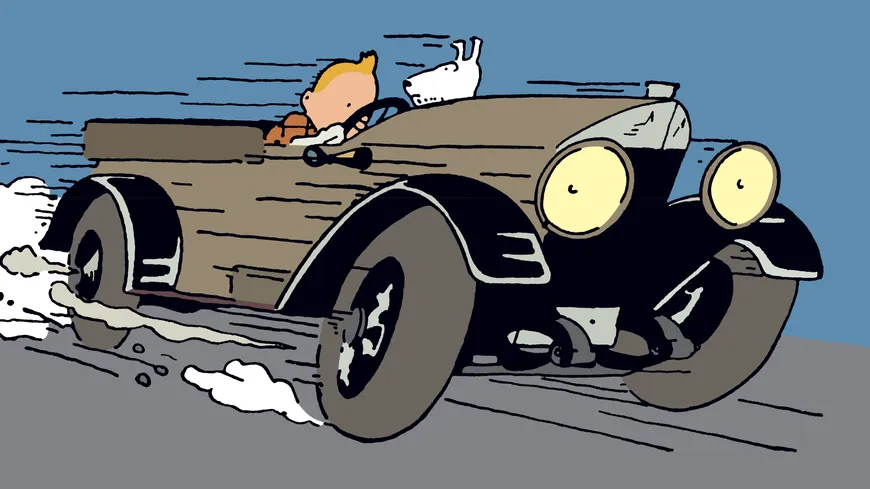

When the opportunity was given me to see the artist Goeun Lee’s two videos, vanish and exist and recovery, a number of thoughts crossed my mind, some about which, I realised when I started reading her personal comments on her works, she had thought of herself, some others that seemed proper to me : the explosion of the hill-top home in Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point, the seventeenth century choice painting topic called “vanity”, the rolling-shutter and the car wheels in Tintin au pays des Soviets, the myth of the “flying gallop” and Eadweard Muybridge’s dismissal of it and what I’ve managed to grasp of the intricacies of filming The Matrix back in 1999.

Recovery, Goeun Lee (이고은)

It goes without saying that the artist Goeun Lee had pondered on the “vanity” style of painting with its Calvinist gloomy recall that life is here only to end: the title “vanish and exist” acts in that respect as a spoiler and the destruction of beauty is what we’ve been summoned to watch in her video. Even more so, the accessory per excellence of the “vanity” style: the skull piercing too soon one day the flesh and hair that had once covered it, which due to its stunning capacity at acting as a protective shell survives with ease centuries of burial, if not millennia, is here itself purposefully shattered by dynamite.

The first time I saw an explosion similar to the one seen in the vanish and exist video in its true time forward unfolding, was in Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1970 film Zabriskie Point (1) where the leading female character, nauseated at the materialistic and counterculture-kids’ murdering consumer society, imagines with glee her boss’ arrogant mansion being repeatedly blown up in the air. There we see for a full three and a half minutes, splinters of débris of whatever items and contraptions are likely to be found in a palatial American home, being shattered in the air in slow-motion. It is that kind of bliss which overwhelms us when being offered to witness ugliness coming to an end.

Zabriskie Point, Michelangelo Antonioni

A vanitas of its own in Antonioni’s film but with the aim in this case of reminding us not so much of the vacuity of an individual life but that of a life-style we may mistakenly have devoted to and wasted on the single life we have been entrusted with – by God knows whom.

And this has guided us to the crux of the matter, whether we think of the films that the artist Goeun Lee produces or the snapshots which can be singled out off them: how does one realise the tour-de-force of generating beauty out of the destruction of beauty ? This is where – as can be expected – the true artist comes in.

In comments made on her own works, the artist Goeun Lee has explained the technical difficulties involved in making objects explode and capturing every single instant of their annihilation. I often get impatient by the end of a film as I can hardly wait to see the bonus feature that is “The making of”, not that I would dislike the end-product but because I wish to know more, a lot more indeed, about two cunning and delightful but up to that point hidden actors: I refer to work and talent, the true protagonists of any masterpiece. The truth is that I like just as well the making of The Matrix as the film itself, capturing time in its tiniest snippets being exactly what it is about in both.

The artist Goeun Lee writes: “The explosions, which are imperceptible to the human eye, are shown in various forms by the rolling shutter (a phenomenon that occurs because the sensor of the shutter is scanned sequentially from top to bottom). Glass and plastic were bent and stretched into unexpected shapes. Images that cannot be seen with the naked eye are reproduced by exploding objects and rolling shutters at a tremendous speed.”

Vanish and exist, Goeun Lee (이고은)

Two dimensions here: “showing the imperceptible” and showing it in a distorted manner as the watching itself by the watcher cannot be extracted, erased, removed, from the picture of the very small, a notion that quantum mechanics has made us familiar with.

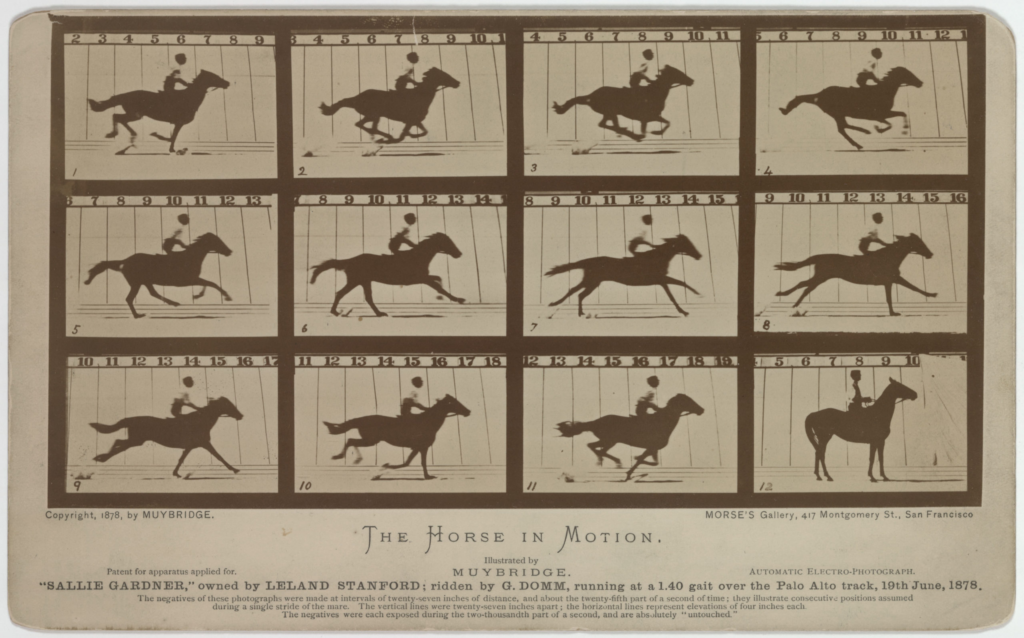

The high-speed shutter having revealed the imperceptible reminds us of course of the “flying gallop”, the classical representation in art of the galloping horse, with his four legs being outstretched, none of his hoofs touching the ground, as can be seen famously in Théodore Géricault’s The 1821 Derby at Epsom (2). Then in the eighteen-seventies came along Eadweard Muybridge’s high-speed photography (3) which dispelled the mirage: the outstretched position is a fancy of the imagination and there is nearly at any time at least one hoof on the ground, a feat that an anonymous Chinese sculptor of the second century AD (4) had been able to capture with his eye as his only apparatus or so it seems at least.

The 1821 Derby at Epsom, Théodore Géricault

The Horse in Motion, Eadweard Muybridge

Flying Horse of Gansu

I hadn’t read the artist Goeun Lee’s remark on the rolling shutter when I watched vanish and exist but it had however come up to my mind: I wrote right away in a note “the car wheels in Tintin au pays des Soviets” (5).

Tintin au pays des Soviets, Hergé

I was only a kid when I saw that but I couldn’t fail to be impressed by that speeding car: there they were, those wheels from snapshots of the thirties, slanting from the top, letting me know unwittingly how fast they were actually spinning. There were no sensors in those days: only mechanical shutters but they were good enough to fool us in believing that our eyes were not only catching distance but the derivative of distance which is speed. The artist Goeun Lee in her technical note informs us that it is the same in her videos and photos: we’re not seeing only magnificent flowers and splendid potteries going to shreds: we’re seeing also, in slow-motion, or even in stills, the speed at which they all metamorphose, in a reversed process, from beauty to annihilation. Nothingness is terrifying indeed. “A chance to think about what we should live for”, writes the artist Goeun Lee in her note on vanish and exist. It could hardly be more aptly expressed.

(1) Zabriskie Point, Michelangelo Antonioni, 1970

(2) The 1821 Derby at Epsom, Théodore Géricault, 1821

(3) The Horse in Motion, Eadweard Muybridge, 1878

(4) The Flying Horse of Gansu, anonymous Chinese sculptor, 2nd century AD

(5) Tintin au pays des Soviets, Hergé, 1930